Authors: Sina Shaikh and Samuel Baltz

Published: November 5, 2024 (2:45pm ET)

In the crucial presidential swing state of Pennsylvania, voters have had the opportunity to cast mail-in ballots for over a month. This has produced an evolving body of data on voter decision-making and election performance. At the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, we have plotted the number of mail-in ballots requested and cast by voters nearly every day since early September, alongside the same information from the 2020 mail and early voting period. We recorded these plots publicly every day, and you can find our entire record of Pennsylvania’s early voting period on most social media platforms (under our handle @MITelectionlab) or online at https://www.elexcentral.org/state-updates/pennsylvania.

In the leadup to the election, we were interested in two main timeseries: the proportion of all requested ballots that had been cast, and the party breakdown of the voters who had returned their ballots. We examined how those data evolved over the course of more than a month, as well as how they compared to the same statistics an equal number of days before the election in 2020. We noticed several patterns that shed light on both the state of the electorate and how to interpret this essential type of administrative data.

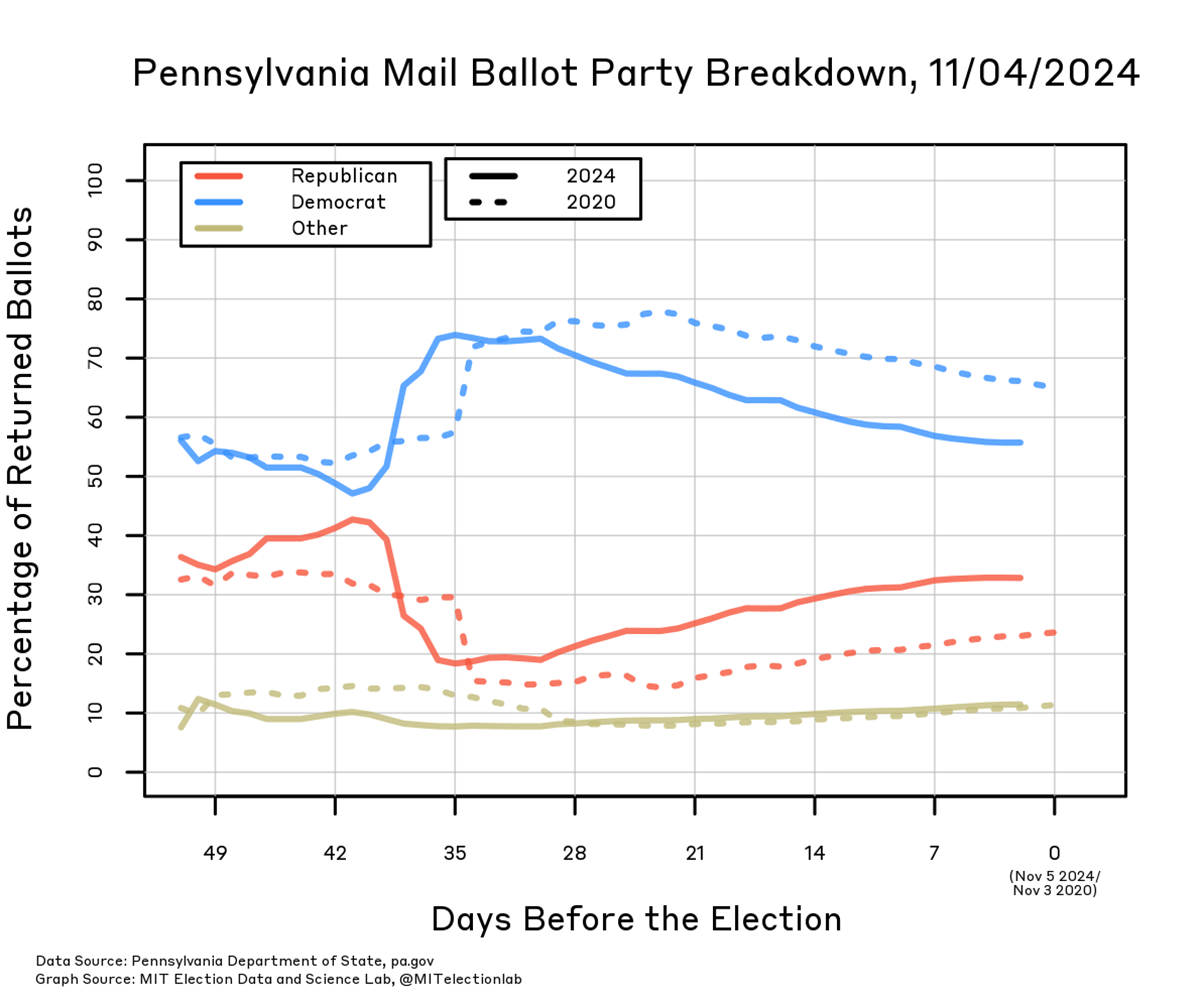

The first trend that we noticed when looking at the party breakdown over time, shown in Figure 1, is how much the party breakdown changed. In both 2020 and 2024, when we look at the data fifty days before the election, about 55% of mail-in ballots had been cast by registered Democrats, and about 35% had been cast by Republicans. By about forty days out, the party shares had converged very close to 50-50, with mail-in ballots cast up to that point barely more likely to come from Democrats than from Republicans. This changed again quickly: the proportions diverged, and by thirty-five days before the election, nearly 75% of mail-in ballots had been cast by Democrats, and less than 20% by Republicans. The share then steadily converged to a split of about 55% Democrats, 33% Republicans, numbers that had largely stabilized by a week or two before the election. So, why is this plot so structured? What caused these shifts in the partisan breakdown of mail-in ballots?

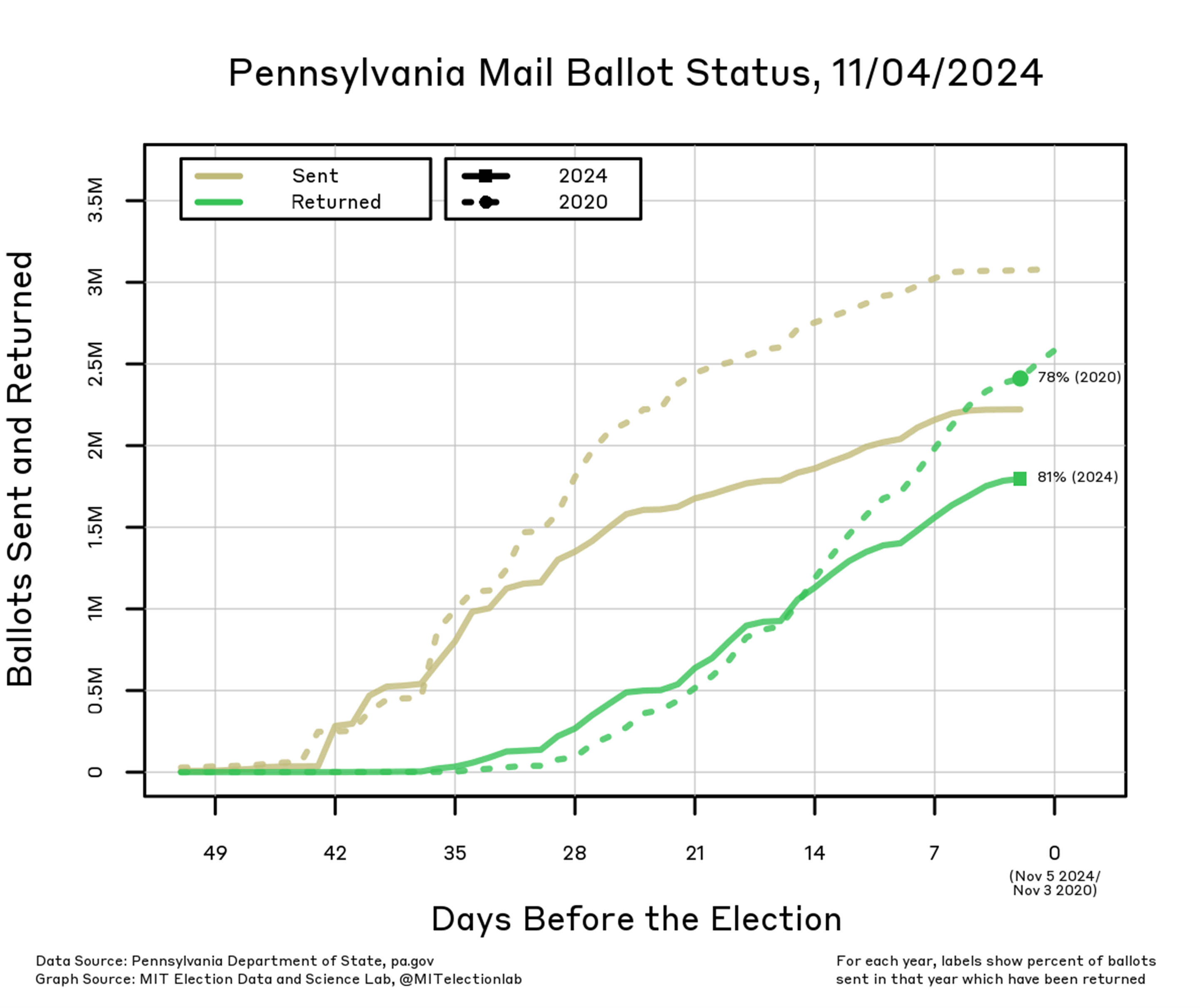

What we discovered is that the plot becomes more informative as time progresses. Fifty days out, the plot has very little meaning; by the end, it means a great deal. Why is that? The key is to consider the volume of mail-in ballots cast over time, shown in Figure 2. The first large-scale return of ballots was about thirty-five days before the election. This is exactly when the partisan proportions suddenly shift as well. Before this point, the number of ballots cast is extremely low: in 2024 only 97 ballots had been sent out 50 days out from the election, and only on October 3 (thirty-three days before the election) did the number of ballots returned reach 100,000.

It is not a surprise that very few ballots were cast more than a month before the election. The first domestic mail-in ballots were sent to voters in mid-September, at most fifty days before the election. Before this period, all ballots that arrived by mail would have come from overseas voters under the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA). The plot suggests that the first large batch of domestic mail-in ballots was sent to voters between forty-three to forty days before the election. As is typical, ballots are not returned in large numbers immediately after they are first sent out, because:

- each ballot must travel through the mail to the voter;

- the voter must finalize their vote choices and cast the ballot;

- the ballot must return back through the mail to the elections office;

- and then its receipt must be recorded and updated in the dataset that we are analyzing.

So, in this case, analyzing information about Pennsylvania’s mail-in ballots would have provided hardly any information until, at the earliest, about a month ahead of the election. We should ignore the left-most part of Figure 1.

Additional Thoughts

A natural question is, if the earliest period captured here only includes UOCAVA ballots, does the left-most part of the figure actually reveal the distribution of party registrations among UOCAVA voters, before the domestic absentee population drowns that signal out? Not necessarily. There is no reason to think that the curve on day forty-three or so has converged to the true partisan distribution among UOCAVA voters, because UOCAVA voters may still (and many do) return their ballots during the period when domestic mail-in ballots are also being returned. The leftmost part of the plot specifically shows the partisan registration among the earliest early-birds of Pennsylvania’s UOCAVA population.

If we should ignore the very beginning of the timeseries, then what should we make of the rest of it? After the domestic absentee ballots begin to be received in earnest, we see only gradual shifts in the party breakdown, but in a very consistent and steady direction: fewer Democrats, more Republicans. This was true in both 2020 and 2024, though the convergence was faster in 2024, and ultimately reached a balance that included more Republicans.

All in all, here are four morsels of food for thought, intended more as scintillating observations about Pennsylvania’s mail-in ballot trends than as definitive pronouncements:

- The absolute earliest early birds of mail-in voting have a roughly even partisan balance. The very first few hundred people to return their ballots, in that very early period when only UOCAVA ballots have been sent to voters, have a much closer partisan balance than domestic mail-in voters overall, who are substantially more likely to be Democrats. This was true both in 2020 and in 2024. However, the number of ballots cast at this stage is so small that the variance in exactly who belongs to this population in a given election may be very large.

- The early birds of domestic mail-in ballots are overwhelmingly likely to be Democrats. With the first 100,000 mail-in ballots in, about 75% had come from Democrats and only about 20% from Republicans. We might imagine (though we haven’t directly tested) that these are people who are extremely motivated to vote by mail specifically.

- As Election Day approaches, the group of people returning ballots on that day becomes gradually more Republican. Almost every day of mail-in ballot returns reduced the Democrats’ lead among mail-in ballots cast, bringing it steadily closer to an even split. Eventually, however, the convergence slowed to a distribution that only somewhat favors Democrats.

- This year the final distribution of party registrations among Pennsylvania’s mail-in voters is roughly 55% Democrats, 33% Republicans. By the time the number of mail-in ballots cast climbed above 1.5 million and the volume of mail ballots cast began to taper off about a week before the election, the party distribution appeared to stabilize. The same thing happened in 2020, but at a lower level of Republican voters.